Bristol Aggie Named 2022 BE+ Green Building of the Year

We are thrilled to announce that Bristol County Agricultural High School received the coveted Green Building of the Year award at the annual BE+ Green Building Showcase! In the largest ceremony since the national Greenbuild conference in 2017, over 225 people gathered to celebrate leading projects in the movement toward a more sustainable and regenerative built environment.

Representing a shift from an agriculture-based curriculum toward one rooted in science and environmental education, the renewed Bristol Aggie campus is both a place of discovery and an instructional tool through its highly sustainable design. From an intensive green roof that doubles as an outdoor classroom to exposed timber structures in three of four new construction buildings on campus, students are invited to engage with the architecture and green technologies on display.

Focus areas on carbon, energy, water, wellness, and equity drove the project and manifest in both the building and landscape design.

Water conservation and reuse strategies reduce campus water usage by 50%

Close ties between the school and the environment are reinforced by outdoor learning and gathering spaces

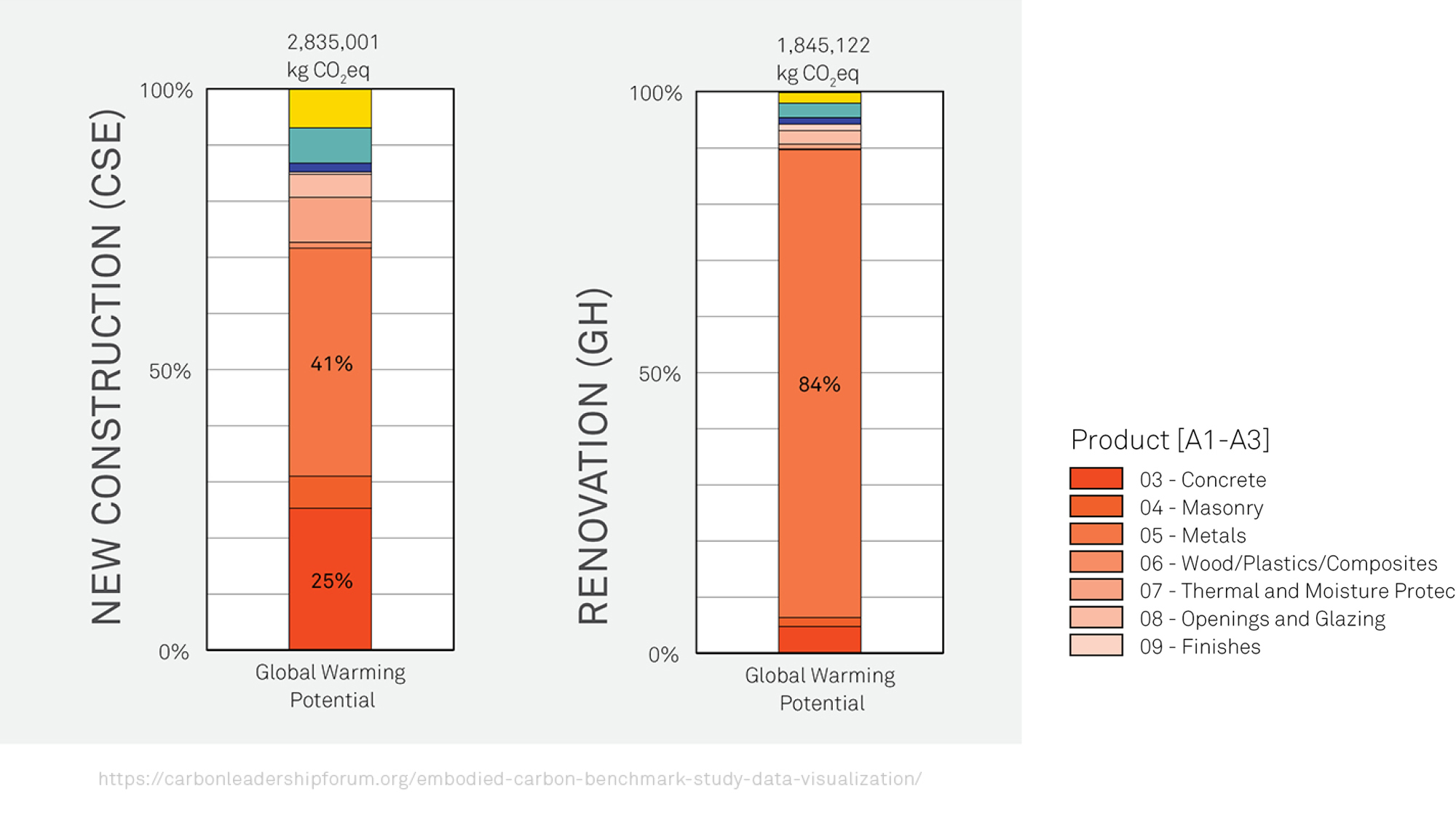

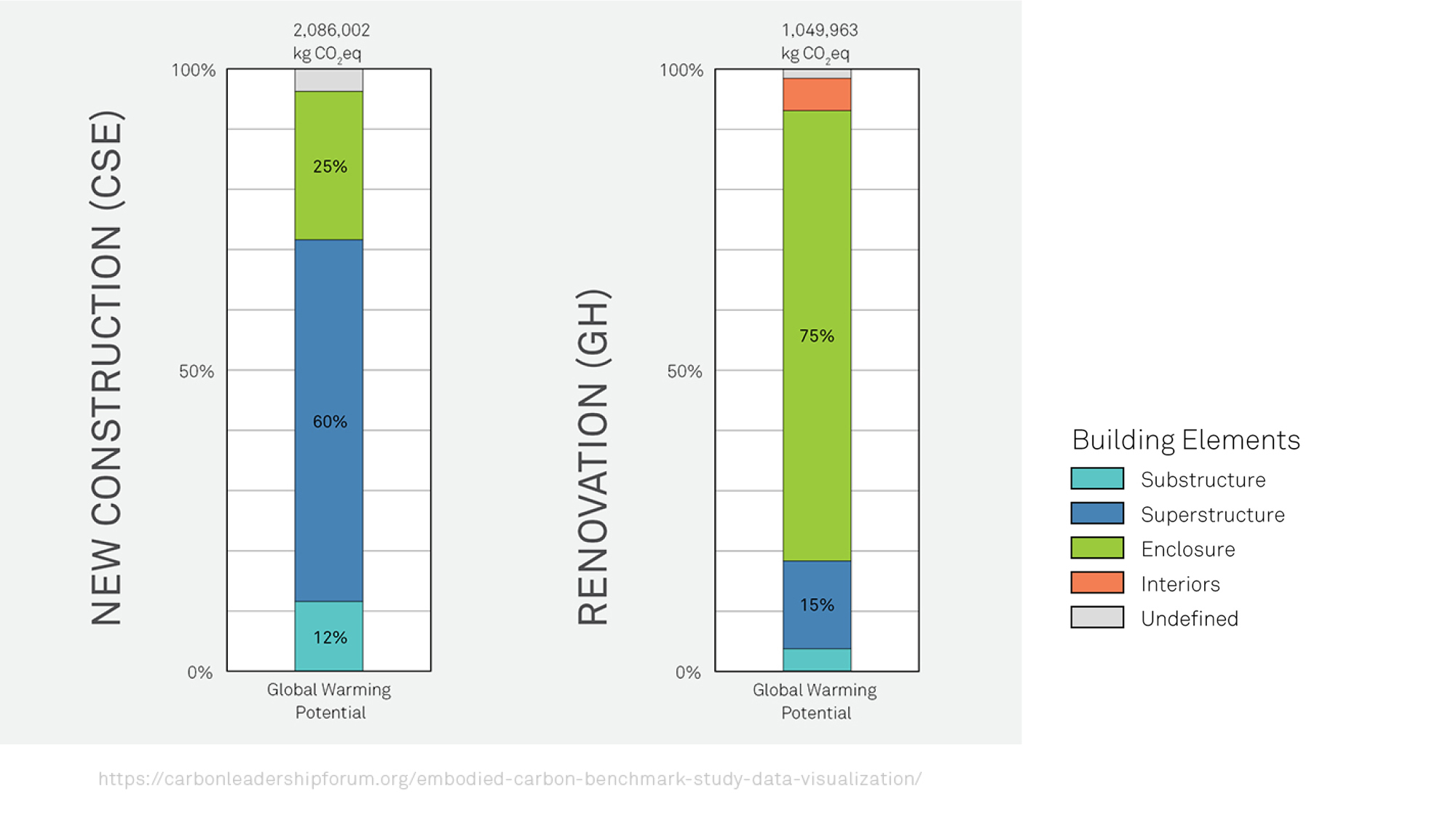

Heavy timber structures sequester 75 metric tons of carbon, while renovating a central academic building avoided 744 metric tons in carbon emissions

All new buildings are designed PV-ready

“The Bristol County Agricultural High School checked so many boxes for us… aggressive sustainability, a strong community connection, a focus on carbon reduction, a teaching tool …all on a limited, public-school budget.”

Jury Comments | Built Environment Plus